Mental health is one of the most common concerns presenting in primary care. In fact, research shows that up to 71% of GP consultations in Australia involve psychological issues of some kind. General Practitioners (GPs) are usually the first point of contact when people seek help, but GPs cannot — and should not — be expected to manage every aspect of mental health alone. That’s where psychologists come in.

A shared-care model , also called collaborative or integrated care, enables GPs and psychologists to work together in a structured way. It ensures patients receive timely, effective, and holistic care that addresses both mental and physical health.

What is Shared-Care in Mental Health?

Shared care refers to planned, structured collaboration between GPs, psychologists, and often other professionals like psychiatrists, social workers, or mental health nurses.

Key features include:

-

Joint treatment planning.

-

Clear role definitions (who prescribes, who delivers therapy, and who monitors progress).

-

Ongoing communication between professionals.

-

Regular outcome measurement and treatment adjustment.

-

Patient-centred care where individual goals guide treatment.

This model is backed by extensive international evidence. Meta-analyses show that collaborative care produces better outcomes for depression and anxiety than usual care at 6–12 months.

How GPs and Psychologists Work Together

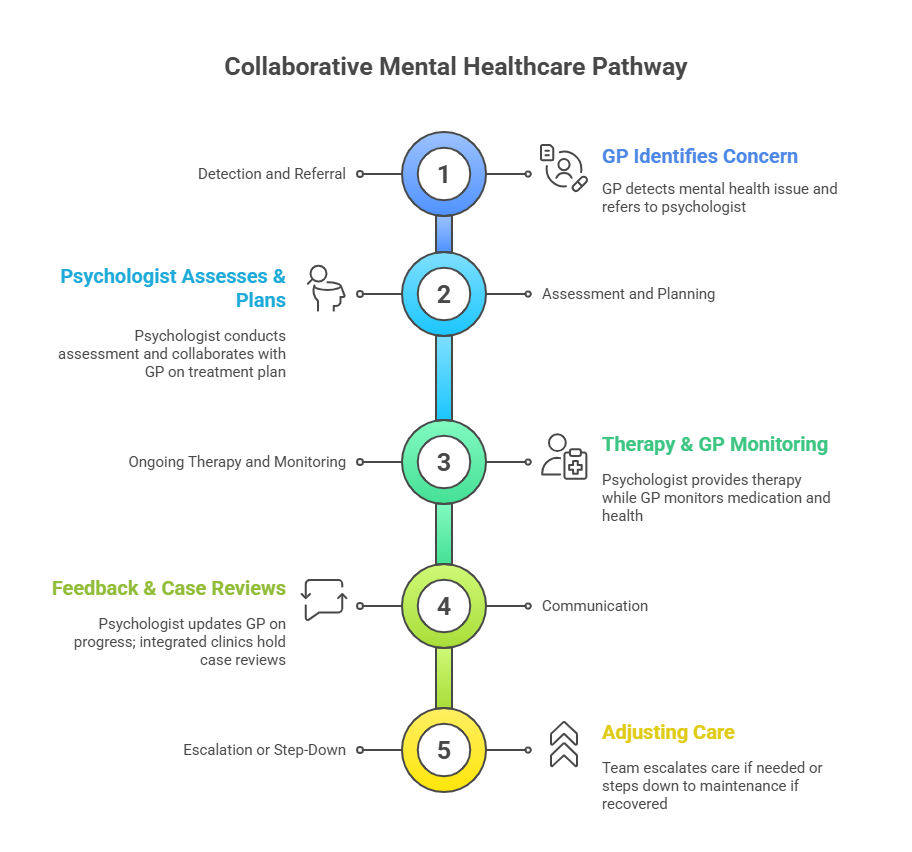

Here’s how collaboration typically looks in practice:

-

Detection and Referral

-

The GP identifies possible mental health concerns during consultation.

-

A referral to a psychologist is made, often under a Mental Health Treatment Plan (MHTP) through Australia’s Better Access program.

-

-

Assessment and Planning

-

The psychologist conducts a detailed psychological assessment.

-

Together with the GP, they align on a treatment plan: therapy, medication, or stepped-care interventions.

-

-

Ongoing Therapy and Monitoring

-

The psychologist provides evidence-based interventions such as CBT, ACT, or interpersonal therapy.

-

The GP may monitor medication, physical health, or comorbid conditions.

-

-

Communication

-

Psychologists provide written updates or feedback to the GP about progress.

-

In integrated clinics, case reviews or joint sessions may be held.

-

-

Escalation or Step-Down

-

If the patient isn’t improving, the team may involve a psychiatrist or intensify therapy.

-

If the patient recovers, care may step down to maintenance or GP monitoring.

-

Evidence for Shared-Care in the Australian Context

Australia has made considerable progress in integrating mental health care into primary practice, and the evidence is clear. Approximately 87% of Australians visit a General Practitioner (GP) annually, with the majority of these consultations addressing psychological issues. This underscores the crucial role GPs play in identifying and addressing mental health needs across the population.

One of the main pathways for collaboration is the Better Access programme, which allows GPs to refer patients to psychologists under a mental health treatment plan, with Medicare rebates available to subsidise sessions. In 2022–23, Australians accessed about 6.43 million subsidised psychology sessions , a slight decline from the previous year, showing both the high demand and the sensitivity of access to policy changes.

Evidence also shows the value of shared care in rural settings , where access can be more difficult. For example, a GP clinic trial involving psychologists, mental health nurses, and visiting psychiatrists demonstrated improved continuity of care and better access for people with mood disorders, substance use issues, and psychotic illnesses. Such models illustrate the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration where specialist services are sparse.

Finally, Australia has embraced stepped care approaches in primary mental health. This means that patients can access low-intensity interventions first, such as guided self-help or brief therapy, with more intensive treatment available as needs escalate. The stepped care model optimises resource utilisation while maintaining treatment responsiveness to individual needs.

Benefits of the Shared-Care Model

Shared care between GPs and psychologists offers significant advantages for both patients and clinicians. Coordinated care consistently improves patient outcomes, especially for depression and anxiety disorders, according to studies. By working together, GPs and psychologists can identify issues earlier, ensure timely treatment, and reduce the risk of conditions becoming chronic. This approach recognises the close link between physical and mental health care and supports their integration.

For patients, shared care also means better access to services, especially when psychologists are co-located within primary care clinics or available via referral pathways like Medicare's Better Access programme. Continuity of care is enhanced, stigma is reduced, and people feel supported by a team rather than having to navigate the system on their own. For GPs, working in partnership with psychologists provides valuable support, helping them feel less isolated when managing complex mental health cases. Together, these benefits contribute to higher levels of patient satisfaction and more efficient use of healthcare resources.

Challenges in the Australian System

Despite its promise, shared care is not without obstacles in Australia. A major barrier is funding. While the Better Access programme provides rebates for psychological services, the gap between rebate levels and actual session costs often leaves patients with significant out-of-pocket expenses. Policy shifts — such as the reduction in subsidised sessions after COVID-19 — have also created uncertainty and criticism from clinicians and consumers alike.

Workforce shortages are another concern. Psychologists are in high demand across the country, with shortages most acute in rural and remote areas. The result creates inequities in access, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and low-income groups. On top of this, coordination and communication challenges persist: different record-keeping systems, unclear role boundaries, and limited feedback loops can reduce the effectiveness of collaboration. Finally, scaling up integrated models requires not only more staff and resources but also cultural shifts within organisations to foster trust and teamwork.

Why Shared-Care Matters for Mental Health

The shared-care model between GPs and psychologists is not just theory — it is already being applied across Australia, from metropolitan clinics to rural GP practices. Programmes like Better Access have made psychological care more available, but system pressures — workforce shortages, policy changes, and inequities — remain barriers.

For patients, the advantages are clear: earlier help, better outcomes, and more coordinated care. For health professionals, collaboration means support, shared responsibility, and the ability to deliver more holistic, person-centred care.

As Australia continues to reform its mental health system, strengthening shared-care models is one of the most promising ways forward.

AUS

AUS can

can